How to stop Nigeria’s oil industry losing relevance

New upstream investment is in fiscal deep water

1 minute read

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon Flowers

Chairman, Chief Analyst and author of The Edge

Simon is our Chief Analyst; he provides thought leadership on the trends and innovations shaping the energy industry.

Latest articles by Simon

-

The Edge

Can emissions taxes decarbonise the LNG industry?

-

The Edge

Why the transition needs smart upstream taxes

-

The Edge

Can carbon offsets deliver for oil and gas companies?

-

Featured

Wood Mackenzie 2023 Research Excellence Awards

-

The Edge

Nuclear’s massive net zero growth opportunity

-

The Edge

Hydrogen: how carbon intensity rules can muddy the waters

OPEC’s biggest producer outside the Gulf and a global heavyweight. Nigeria’s industry has been on the go since the 1950s and there’s a big prize still to be had in deepwater. We estimate 10 billion boe in undeveloped deepwater resource, perhaps the same again in yet-to-find. Geologists acknowledge the best reservoirs as world class.

Yet Nigeria is losing its relevance for Big Oil. Ten years ago, it was the most valuable country position by NPV in Shell’s global upstream portfolio. Today it’s fifth, has slipped in the rankings for Chevron and Eni too, and barely scrapes into ExxonMobil's top 10. Only for Total is Nigeria in the top three.

The country’s growth prospects looked rosy a decade ago. We forecast oil production would surpass 3 million b/d by now, as discoveries in the emerging deepwater play were developed. That just hasn’t happened with volumes barely climbing above 2 million b/d. Too few of these discoveries are being developed. Gail Anderson, Upstream Research Director, identifies the main reasons why Nigeria is under-delivering.

Global deepwater project costs have fallen by as much as 50% since then and now average under US$10/boe for 2018 FIDs.

First, the industry has been dogged by uncertainty for a decade - the kiss of death for investment.

Reform has been on the agenda since 2008, the government aiming to increase its fiscal share from deepwater fields. The rejection of the Petroleum Industry Governance Bill in July is not a good sign that the wide-ranging Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) will be settled any time soon. It’s like Waiting for Godot, putting the kibosh on deepwater exploration and investment, exacerbating the effect of the oil price crash.

Second, costs are high compared to other deepwater provinces.

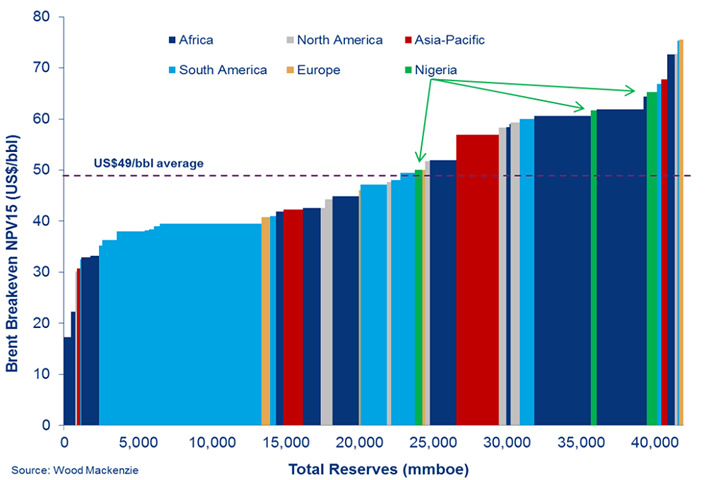

Nigeria has a pre-FID hopper with giant discoveries like Owowo (700 million barrels) and Bonga SW (600 million barrels). But these have not progressed down the cost curve as might be expected during the downturn (see chart). This contrasts with other deepwater territories around the globe where there’s a new crop of lower breakeven greenfield projects.

Nigeria's demanding local content law has restricted scope for cost reduction. The Egina project is a rare example of a new development and is due on stream by end-2018. Operator Total has cut drilling costs by up to 60%; but overall capital costs still weigh-in at US$24/boe, 20% above the peer group average for deepwater projects sanctioned in 2013. Global deepwater project costs have fallen by as much as 50% since then and now average under US$10/boe for 2018 FIDs.

Third, there's the fiscal risk.

With no PIB in sight, the clock is running down on Nigeria's current deepwater production sharing contracts (PSCs), which start expiring over the next five to ten years. IOCs won’t invest in new large-scale projects when there's zero visibility on fiscal terms for much of the asset’s life. The lack of clarity and action contrasts with countries that have been willing to change fiscal terms to attract a shrinking pool of investment. Angola‘s collaborative approach with industry led to improved terms for smaller deepwater fields, and new spend.

A comprehensive overview of Nigeria's upstream industry

Nigeria upstream summary

Purchase the full reportSo what has to happen to get the industry investing in Nigeria’s huge undeveloped deepwater resource and halt a steep production decline post-2020?

One option is to renegotiate terms of the PSCs now, ahead of expiry. ‘Nigeria Inc.’ would get a higher fiscal share immediately; IOCs would get clarity of fiscal terms for 20 years. The big question is whether fiscal clarity on its own is incentive enough. They might prefer to harvest their current projects and leave.

Flexibility on development and costs could square the circle. Project optimisation, reduced lead times, phased development, faster drilling, and better project execution have lowered break evens and sparked a new phase of investment in deepwater Brazil, Gulf of Mexico, Guyana and other arenas. Innovative development models will bring down costs and make Nigeria competitive again. The government can expedite change in this direction.

The country needs a new approach to deep water. It may be the only way to get the IOCs to invest in Nigeria for a few decades more and stop the slide down the portfolio rankings.